A Systematic Assumption: Unhiding the Theological Elephant in the Room

Systematic theology is often championed as the apex or pinnacle of thought in Christian circles. And while some may espouse a more focused appeal to biblical theology as being more robust than systematic theology, the net propositional reality remains the same. Both inherently strive to keep the proverbial elephant out of sight and hidden from the apperceptive and cognitive engagement of one’s mind.

Such a statement does not presuppose any duplicitous motive or a desire to subversively control the masses. On the contrary, theology is ordinarily pursued by individuals with a genuine desire to have a deeper relationship with God, to comprehend His word, and to help others understand the biblical message with greater clarity. In short, an inquiry into theology is ultimately an altruistic endeavor.

To voice an underlying assumption requires that we understand the net impact of its application prior to delving into the particulars of the assumption. This requires a brief explanation on the supposed nature, purpose, and the permutations of systematic theology.

The Nature and Purpose of Systematic Theology

The nature of systematic theology is largely described as a heuristic approach to the study of God and the structuralists’ generative organization of first principles, conceptual priorities, and hierarchical taxonomies that externally and internally cohere with the entirety of the biblical canon and human experience.

In addition to serving as an aid to knowing and worshiping God more intimately, the purpose of systematic theology, and indeed theology in general, is to coherently and succinctly outline and organize truth claims about God, humanity, and the divine plan for all creation.

Systematic theology is therefore intended to serve as both a heuristic method and measure by which doctrinal claims of truth about revelation, the ineffable, and the practical are articulated, reasoned, and believed.

The Emerging Problem

At this point, we begin to see a problem emerge. The pursuit of systematic theology aspires to be the method for articulating scriptural truth while also serving as the measure (or standard) by which the truth is reasoned as accurate.

The method circularly reaffirms itself because the measure is congenitive to and conflated with the method.

The problem is further enhanced by the diversity and disparity between the numerous systematic theologies—all of which pull from the same texts with vastly different claims of truth, while relying on their congenitive and conflated heuristic as providing sufficient and salient validation for the legitimacy of their claims.

Soteriological Examples of Disparity

A pertinent example sufficiently illustrates the disparity and permutations of systematic theology in the main. Perhaps the most well-known case rests on the topic of soteriology; that is, on the topic of grace. The following five theological systems hold five different doctrinal views:

- Arminianism teaches resistible grace – God gave prevenient grace to all, which endows all people with the ability to accept salvation.

- Calvinism embraces irresistible grace – God’s grace is given to those He elected and predestined for salvation.

- Lutheranism addresses universal grace – God’s grace is given to all and it is incumbent on the individual to accept salvation.

- Molinism adopts overcoming grace – God’s grace overcomes human depravity as long as people choose to accept salvation.

- Provisionism espouses illuminating grace – God illuminates the soul, giving people the sufficient ability to accept salvation.

To be sure, the comparative list is not exhaustive. In fact, even in these systems we find further systematic permutations, such as:

- Remonstrant Arminianism

- Wesleyan Arminianism

- Hyper-Calvinism

- Neo-Calvinism

- Neo-Lutheranism

Additionally, there are theological systems that either share affinity with particular denominations or adhere to specific organizational nexuses, such as:

- Catholic

- Covenant

- Dispensational

- Dogmatic

- Liberal

- Orthodox

- Pentecostal

- Reformed

- Wesleyan

All of these systems assert a particular (textually reasoned and methodologically argued) view of soteriology that is measured (or tested) against itself as a congenitive part of the entire system in order to determine the soundness and validity of the soteriological proposition.

For example, a rebuttal to a particular view of grace also demands addressing the system’s understanding of:

- The sovereignty of God

- Theodicy

- Divine responsibility

- Providence and concurrency

- Justification and redemption

- Original sin and the consequence of depravity

- Human initiative

- Limits of agency

- Progressivism and the ethics of chronological snobbery

- Basic principles of hermeneutics and reader-response criticism/interpretation

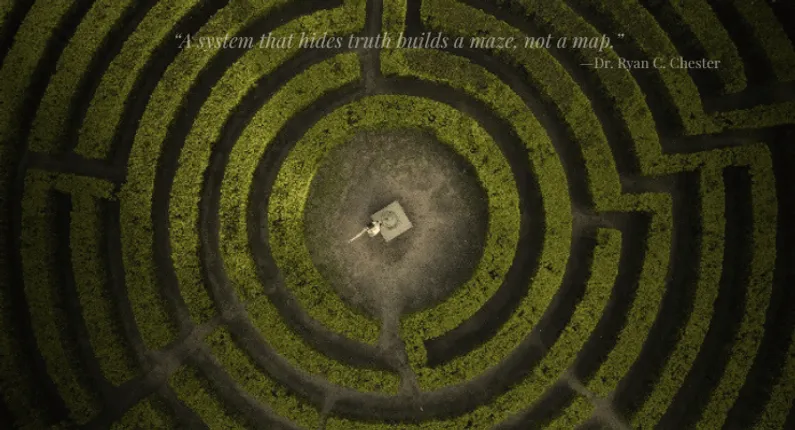

All of these, and more, must be methodologically balanced and cognitively reasoned given the underlying architecture of assumptions in the system. In other words, counterarguments are dismissed in the system because the system is invested in confirming itself. The hidden elephant remains hidden.

The Elephant in the Room

What then remains hidden in the system of theology? What is this proverbial elephant in the room?

The circularity of designed methodology and conflated measure partially exposes the problem. The elephant in the room hides in the assumption of human right, authority, and ability to perform the idealized task of systematic theology.

Simply put, the assumption is perhaps best framed in ironic, rhetorical terms:

Systematic theology is a human attempt to synthesize, organize, and prioritize what they think that God thinks are the most important parts of His indivisible, unchangeable, and univocal word.

It is a presumptuous effort to assume that humanity has the ability to accurately transform God’s word into a truncated system of processed and ranked doctrinal priorities.

It is equally rash to assume that humanity has the ‘inside scoop’ on God’s thoughts pertaining to what He deems is the most important and necessary knowledge vs. the aspects of His word that are unnecessary.

This line of reasoning suggests a contradictory view of Scripture. To be sure, systematic theologians do not suggest such a view. However, if the elephant in the room is permitted to speak, wouldn’t the above line of thought trumpet such a proposition?

The Scriptural Perspective

All too often, systematic theology is heralded as a conclusion rather than as an elementary introduction. Most theologians can agree that:

- God’s word is indivisible (Deut 4:2–8; 12:32; Prov 30:5–6; 2 Tim 2:15; Rev 22:18–19).

- God’s word, like His being, is unchangeable (Ps 119:89; Isa 40:8; 55:8–11; Mal 3:6; Matt 5:17–20; 24:35; 1 Pet 1:24–25).

- God’s word in its entirety is the univocal expression of one divine message (Deut 5:22; Ps 19:1–14; John 1:1–5, 14–18; 2 Tim 3:16–17; Heb 1:1–2).

With such an understanding, the Scriptures self-attest that no part of God’s word is more important than any other. While Matt 22:36–40 attests to an authoritative rank, this must not be understood as a process or system but as a relational attitude that reflects the heart’s ultimate desire to worship God alone and, in so doing, edify others who are made in His image.

Conclusion

Rather than debating which theological system is better, perhaps we should recognize that the system we treasure most is fundamentally flawed because we are fundamentally broken in our trespasses and finite in our understanding.

Systematic theology does have its place pertaining to elementary matters. Therefore, let us concede that no systematic theology can accurately perform the task of condensing Scripture, whose systematic theology is already sufficiently condensed in every word of the final form of the sixty-six books of the Bible.