When Questions Answer Themselves: The Hidden Trap of Language

“Was Socrates a man?”

The question, framed with the cultural and conceptual milieu that spans more than two thousand years of history, guarantees the truthfulness of the answer in the question. Over two thousand years of philosophy, literature, and pedagogy have constructed the frame where “Socrates” is inseparable from “man.” The question does not invite investigation into his being; it merely reaffirms the conceptual scaffolding already accepted by history and culture. The answer (“Yes”) is guaranteed not by reasoning through the question but by the cultural inheritance that has already answered it in advance. By invoking “Socrates,” the question summons a universe where “man” is unavoidable.

This question is framed as a Self-Answering Tautology, where the question supplies the answer from within. In formal logic this is called a tautology: a question that smuggles its answer and permits no alternative**.**

This essay exposes how such questions masquerade as wisdom, why they strangle reasoning, and where they appear in daily life.

When Grammar Pretends to Offer Choice

Now shift the frame: Is history a treatise on the past or a treatise on the future? Even if we assume the question is static and devoid of context, the question presupposes one truthful answer of “Yes.” To be sure, this question commits an error in the form of a complex question of equally weighted truth values, for one could answer “Yes” to one question and “No” to another question. However, even if we strip the question from any context, the question presupposes a single answer: “Yes.” It commits the complex-question error: each half could be answered differently, yet the combination coerces affirmation.

The question is overtly framed as a disjunctive of comparison by the word “or,” which frames a binary that only performs choice. But because the question frames two truthful phrases about the same subject and verb, it annuls the force of the disjunctive and treats both phrases as epistemological truth.

The “or” pretends to offer a choice but collapses into tautology.

Both options reinforce the same outcome, making the question self-sealing. The “or” performs choice while denying it.

Identity, Motivation, and Morality

Identity tautologies prey on time itself: Is who you are becoming more important than who you have been? Can one really claim that you as the prime subject are any less important than who you were, who you are, and who you will be? You are the same subject. To assert such a claim presumes to devalue either you in the past or you in the future, which is to presume that you have the license to divide yourself and assign a different value on the parts. The question pretends to weigh future self against past self. To prioritize one temporality over another is to deny that continuity, while simultaneously affirming it (since it is you in every case). Thus, any answer collapses into a tautology: “You are you.”The valuation exercise cannot escape redundancy because it is bound to the same subject.

Motivational slogans may be the worst offenders. For example: Can you ever lose by investing in yourself because you are your greatest asset? The question presupposes both the value (you = greatest asset) and the outcome (investment = no loss). Thus, it collapses into tautology: the conclusion is smuggled in by the premise. On the surface, it looks like an ethical, motivational, or strategic inquiry. But structurally it denies inquiry, because the predicate (“greatest asset”) already closes the evaluative loop. It also creates the illusion of wisdom while masking the deeper reality: investment can be misdirected, destructive, even eroding. This fallacy is grounded in a motivational-economic frame where the value premise (“you are your greatest asset”) forecloses the question. The tautology arises because the metaphor of “asset” already guarantees positive return in the question’s own terms. This is an example of a teleological tautology. It smuggles in an assumed end (investment must yield gain) and then frames the subject (the self) so that no alternative outcome is conceivable. The assumed end defines the means before the question is asked.

The metaphor of “asset” guarantees decision bias in advance.

Other questions wear moral clothing: Is success without fulfillment the ultimate failure? At first glance it sounds profound, even moral. But notice: the question defines “success without fulfillment” as failure by another name. It imports its answer in the way it equates categories. It frames opposites (success vs. failure) in such a way that one is simply declared to be the other. The question masquerades as a dilemma, but the premise already annuls the distinction. In effect, the tautology is: “Failure is failure, even when it looks like success.” It feels probing, but it isn’t inquiry. It’s a linguistic trick. You can only answer “Yes” without contradicting yourself, because the categories have been rigged. It bypasses the real philosophical work of defining fulfillment, measuring success, or exploring whether they can exist apart.

Leadership, Justice, and Culture

Leadership clichés carry their own trap: Can you call yourself a leader when no one grows while you’re around? The definition of “leader” implicitly includes growth, development, or influence on others. By embedding “no one grows” into the question, it nullifies the very category of leadership. The only possible truthful answer is “No,” because the premise already disqualifies the subject. Leadership is inseparable from growth. If growth is absent, the attribute of “leader” is self-contradictory.

The stakes grow sharper in ethics: Can justice ever be just if it is not applied equally? The word “justice” is already defined by impartiality and evenhandedness. To ask whether justice can exist without equality is to smuggle the answer inside the question. The only possible truthful answer is “No,” because denying equality cancels the very definition of justice.

Unequal justice is not justice. It is preference dressed as law.

Modern culture is riddled with similar traps. Political debates ask questions like, “Isn’t freedom just the ability to choose?” Corporate speeches frame slogans like, “Innovation is progress by definition.” These questions sound profound, but like the others, they cancel inquiry before it begins.

Mapping Tautologies by Type

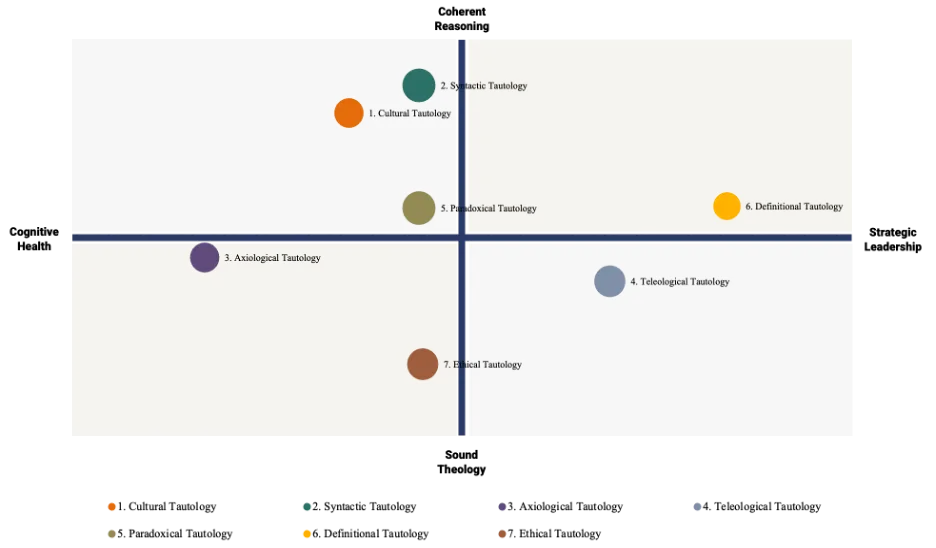

These tautological questions can be classified into seven types and mapped by the four dominant categories of thought. This sits inside coherent reasoning and critical thinking: question framing and cognitive linguistics matter because language shapes inference. The model below shows how each tautological question anchors to the compass: coherent reasoning in the north, strategic leadership in the east, sound theology in the south, and cognitive health in the west. Each tautology fails at the very point it claims to uphold as the following relationship map demonstrates.

Tautologies by Equation

The seven tautological questions identified and mapped above are summarized below. Each type is reduced to an equation for quick reference: a question, its illusion of depth, and the way it collapses into self-reference.

Cultural tautology — truth fixed by history or culture

- Question: “Was Socrates a man?”

- Explanation: The cultural and historical milieu already guarantees the answer. Centuries of philosophy and pedagogy have fixed “Socrates” and “man” as inseparable.

- Equation: Socrates = cultural tautology (the weight of history makes the answer inevitable).

Syntactic tautology — truth fixed by grammar or definition

- Question: “Is history a treatise on the past or a treatise on the future?”

- Explanation: The disjunctive “or” collapses both options into a single affirmation; grammar annuls choice.

- Equation: History = syntactic tautology (the grammar annuls the binary, forcing affirmation).

Axiological tautology — truth fixed by indivisible value of the subject

- Question: “Is who you are becoming more important than who you have been?”

- Explanation: You are the same subject across past, present, and future. To prioritize one temporality over another is to deny continuity while affirming it.

- Equation: Self = axiological tautology (worth cannot be divided across past, present, and future without contradiction).

Teleological tautology — truth fixed by the assumed end or outcome

- Question: “Can you ever lose by investing in yourself because you are your greatest asset?”

- Explanation: The metaphor of “asset” guarantees gain in advance. The conclusion (investment = no loss) is smuggled into the premise.

- Equation: Investing in yourself = teleological tautology (gain is assumed before the act is examined).

Paradoxical tautology — truth fixed by collapsing apparent opposites

- Question: “Is success without fulfillment the ultimate failure?”

- Explanation: The categories collapse: “success without fulfillment” is simply declared failure by definition. The appearance of contrast hides redundancy.

- Equation: Success without fulfillment = paradoxical tautology (success is declared failure by definition).

Definitional tautology — truth fixed by the category’s own definition

- Question: “Can you call yourself a leader when no one grows while you’re around?”

- Explanation: Leadership already implies growth. By embedding “no one grows” into the question, the category cancels itself.

- Equation: Leader without growth = definitional tautology (leadership is canceled by its own premise).

Ethical tautology — truth fixed by virtue measured against itself

- Question: “Can justice ever be just if it is not applied equally?”

- Explanation: Justice is defined by impartiality. Denying equality cancels the very concept.

- Equation: Justice without equality = ethical tautology (denying equality cancels justice in advance).

Every tautology masquerades as inquiry while denying discovery.

Commonplace Tautologies

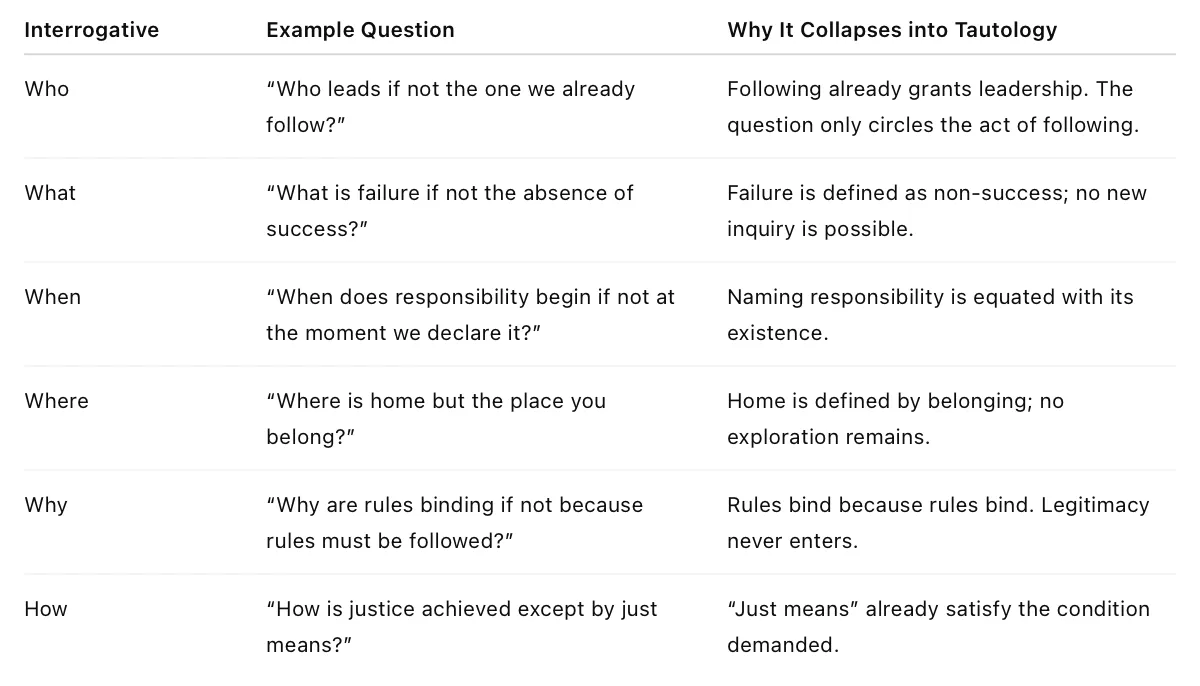

Tautologies are not confined to philosophy. They hide in ordinary interrogatives: the Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How of daily speech.

While the tautologies in this article focus on the problem of question framing, the same problems occur in ordinary speech. By dropping the interrogative question one may immediately identify the same fallacy in declarative statements. If we take the tautology that wears moral clothing and drop the interrogative as an example we can see how empty the statement really is: Success without fulfillment is the ultimate failure. The tautology asserts that agreement is the only answer. But this, like the question, is a linguistic trick. The problem with these questions and statements is that they appear profound while being inherently devoid of value.

Quick Test for Tautology

If every question smuggles its own answer, truth has no chance.

The discussion illustrates the importance of framing questions well and the dangers of posing questions that appear profound. A better approach is to audit the question in advance by applying the following steps:

- Does the question define its own outcome?

- Is the “or” doing real work, or only performing choice?

- Can I name an external object or condition that could falsify the answer?

In your next meeting, test one question: does it invite discovery or perform certainty? Change the question, and you open the mind.

While tautological questions are erroneous in structure, they are not always useless in practice. Was Socrates a man? is an appropriate question for a child, because it introduces cultural memory and logical affirmation. Is history a treatise on the past or the future? might be staged to teach the error of shallow binaries. Yet outside of pedagogy, such framing is usually not innocent. It is employed to sound profound and seize attention without offering substance. That is why tautologies are dangerous: they mimic wisdom while forbidding inquiry.